What are Probiotics?

Probiotics are the beneficial bacteria that inhabit our bodies. They can assist with digestion, immunity, brain function, metabolism, sleep and neurotransmitter production to name but a few areas of health. Some can inhibit and crowd out pathogens too. In essence, they are a cornerstone of good systemic health.

“Probiotics are live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.”

-The International Scientific Association for Probiotics & Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope & appropriate use of the term probiotic.

There are many intriguing questions yet to be answered and the science is provisional, so when below, I associate a benefit with a particular bacterial strain, that’s what recent research has suggested. Despite a great many studies, no health claims for probiotics are yet permitted by regulatory authorities in the UK or Europe.

Research is challenging because each of us has a unique community of microorganisms living in and on us (the microbiome) and it has been shaped by diet, exercise, age and stress. Some good quality research into the benefits of certain bacterial strains, is now emerging however.

Some common bacterial strains & what research suggests about their benefits

Lactobacillus (actually over 200 species) is naturally present in the gut, mouth and vagina (3). It can help preserve gut barrier integrity, modulate the immune system and help guard against digestive discomfort. It converts sugars to lactic acid, creating an acidic environment which limits pathogens. In the gut, it produces vitamin K2 (3) which helps guide dietary calcium to our bones, so it may be useful in osteoporosis.

Lactobacillus acidophilus can stick to the intestinal wall and prevent overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria. It may help acute gastroenteritis, as in food poisoning, and may shorten the duration of diarrhoea (4). It may help IBS (5).

Lactobacillus rhamnosus (now renamed Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, although probiotic product labels often still use the old name) can benefit gut resilience, vaginal health and IBS. It may be as helpful for bloating as a low FODMAP diet (6). It may provide cognitive support in older adults (7). It may also enhance sleep duration and efficiency. A small four week trial suggested it helped students with exam stress (1). It may also help diarrhoea associated with both travel and a course of antibiotics (2).

Lactobacillus plantarum benefits immune equilibrium, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines. It may benefit healthy adults, and also those whose overall health comes under mild stress, from students to athletes (8). It has been associated with small improvements in fasting glucose and insulin stability so may be helpful in type 2 diabetes. It may give a modest reduction in visceral fat ie the fat which is deep in your abdomen surrounding your vital organs, and higher levels of which are unhealthy.

Bifidobacterium (9) may help us digest fibre and produce short chain fatty acids which are good for health. It may assist with gut barrier integrity, immune modulation and healthy ageing.

Bifidobacterium bifidum may adhere to the intestinal lining and ease us through digestive issues brought about by travel or dietary changes. It may assist with chronic constipation and combat an overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria, namely some strains of prevotella, which have been associated with inflammation and autoimmune disease.

Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis may help with stool frequency and consistency. It survives stomach acid, and seems useful for immune balance in later life. For acid reflux, it may be as good as PPI drugs eg omeprazole (10).

Bifidobacterium longum may improve sleep quality (11).

One more strain that may be of interest is streptococcus thermophilus because it supports the growth of lactobacillus and bifidobacterium. It may also aid lactose digestion in those people with mild intolerance, and promote immune system balance.

I’m interested in a particular bacterial strain: which products would I find it in?

One or two particular benefits in the above lists may have caught your attention, so let’s look and see what is contained in some easily-available supermarket products: Yeo Valley yoghurt, Onken yoghurt, Biotiful kefir, and if you’re dairy-free, The Coconut Collab yoghurt.

Four products found in most supermarkets

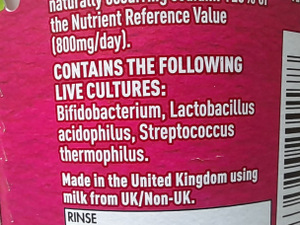

Yeo Valley yoghurt is labelled as containing bifidobacterium, lactobacillus acidophilus and streptococcus thermophilus.

.

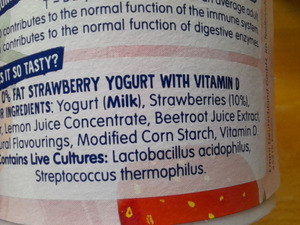

Onken yoghurt is labelled as containing lactobacillus acidophilus and streptococcus thermophilus.

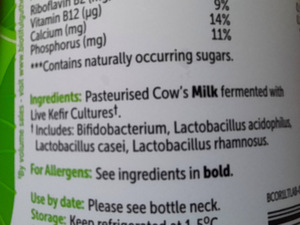

Biotiful kefir is labelled as containing lactobacillus acidophilus, lactobacillus casei, lactobacillus rhamnosus and bifidobacterium.

Dairy-free option:

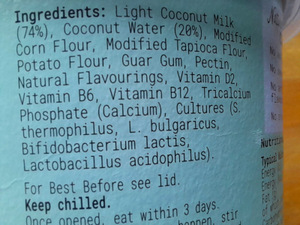

Coconut Collab yoghurt is labelled as containing lactobacillus acidophilus, lactobacillus bulgaricus, streptococcus thermophilus and bifidobacterium lactis.

I’ve confined this small review to fresh products found in the chiller cabinet rather than bacteria capsules that come in a bottle. My preference is for real food where appropriate.

My suggestion would be you simply experiment. If you haven’t had any probiotic products before, start with small quantities daily and anticipate a possible alteration in your bowel habit as your microbiome adjusts.

References

(1) Probiotic-mediated modulation of gut microbiome in students exposed to academic stress: a randomized controlled trial. nature: npj biofilms & microbiomes, 21 July 2025.)

(2) The Potential Impact of Probiotics on Human Health: An Update on Their Health-Promoting Properties. Microorganisms, 23 January 2024.)

(3) Importance of Lactobacilli for Human Health. Microorganisms, 21 November 2024.)

(4) A Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis: Lactobacillus acidophilus for Treating Acute Gastroenteritis in Children. Nutrients, 6 February 2022.

(5) A 2-strain mixture of Lactobacillus acidophilus in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Digestive & Liver Disease, May 2020.)

(6) Ehealth: Low FODMAP diet vs Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in irritable bowel syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 21 November 2014.

(7) Cognitive and Emotional Effect of a Multi-species Probiotic Containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium lactis in Healthy Older Adults: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial. Probiotics & Antimicrobial Proteins, 27 June 2024.

(8) Meta-Analysis: Randomized Trials of Lactobacillus plantarum on Immune Regulation Over the Last Decades. Frontiers in Immunology, 22 March 2021.

(9) Bifidobacteria and Their Role as Members of the Human Gut Microbiota. Frontiers in Microbiology. 15 June 2016.

(10) Efficacy of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp.lactis BL-99 in the treatment of functional dyspepsia: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. nature – nature communications, 3 January 2024.

(11) Bifidobacterium longum 1714 improves sleep quality and aspects of well-being in healthy adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. nature – scientific reports, 14 February 2024.

Here, I offer you a brief insight into ancient Chinese wisdom, and show with the aid of some examples, how well it resonates with the results of modern medical research. If you take away a flavour of this short article and change just one thing in your life as a result, then your time reading it will have been well spent.

Here, I offer you a brief insight into ancient Chinese wisdom, and show with the aid of some examples, how well it resonates with the results of modern medical research. If you take away a flavour of this short article and change just one thing in your life as a result, then your time reading it will have been well spent.

Diet is a cornerstone of good health. Chinese medicine can guide not only what we eat, but how we eat it. The ancient Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine, advised “The five cereals are staple food; the five fruits are auxiliary; the five meats are beneficial; the five vegetables should be taken in abundance.” 2500 years later, these priorities resonate strikingly with the UK’s “5-(portions of fruit & veg) a-Day” campaign. Over the centuries, subsequent texts reveal sophisticated developments in the use of food, including the transition to cooked food, made possible by drilling wood to create fire. Yi Yin in the Shang dynasty (BC1600-1046) emphasised that physicians should use the right kinds of food to help cure disease; food had now become equal to medicine.

Diet is a cornerstone of good health. Chinese medicine can guide not only what we eat, but how we eat it. The ancient Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine, advised “The five cereals are staple food; the five fruits are auxiliary; the five meats are beneficial; the five vegetables should be taken in abundance.” 2500 years later, these priorities resonate strikingly with the UK’s “5-(portions of fruit & veg) a-Day” campaign. Over the centuries, subsequent texts reveal sophisticated developments in the use of food, including the transition to cooked food, made possible by drilling wood to create fire. Yi Yin in the Shang dynasty (BC1600-1046) emphasised that physicians should use the right kinds of food to help cure disease; food had now become equal to medicine. Finally, there is how we eat. Never skip breakfast. “People who eat breakfast are significantly less likely to be obese and suffer from diabetes than those who usually do not.” (American Heart Association’s 43rd Annual Conference on Cardiovascular Disease & Prevention). The emerging field of

Finally, there is how we eat. Never skip breakfast. “People who eat breakfast are significantly less likely to be obese and suffer from diabetes than those who usually do not.” (American Heart Association’s 43rd Annual Conference on Cardiovascular Disease & Prevention). The emerging field of